Abstract

We present a case of a 16-year-old male who sustained a blunt head injury during a physical altercation, resulting in a subacute subdural hematoma (SDH) and a subgaleal hematoma over the left temporal region. The patient initially experienced transient loss of consciousness, followed by persistent headache, nausea, and vomiting. Upon radiological evaluation, a localized subacute subdural hematoma and associated subgaleal hematoma were identified. Conservative management was pursued, as the hematomas were small, without evidence of midline shift or raised intracranial pressure (ICP). The patient was successfully managed with supportive treatment and discharged with outpatient follow-up.

Introduction

Head trauma remains one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the pediatric and adolescent populations worldwide. While most minor head injuries are self-limiting, some cases may progress to serious complications such as intracranial hemorrhage, including subdural, epidural, or intracerebral hematomas. Subacute subdural hematoma typically occurs several days following trauma and may present with nonspecific symptoms such as headache, nausea, and vomiting. Timely recognition and appropriate management are crucial to prevent long-term neurological damage. This case report discusses the clinical presentation, diagnostic evaluation, and management of a 16-year-old boy with a subacute subdural hematoma and an associated subgaleal hematoma following blunt head trauma

Case Presentation

Patient History

A 16-year-old male was brought to the emergency department by his family after developing persistent headache and episodes of vomiting for several days following a physical fight with a peer. During the altercation, the patient was struck on the left side of his head with a stone. Witnesses reported that he lost consciousness for approximately 10 minutes at the scene but spontaneously regained consciousness without any immediate focal neurological deficits. Initially, the family did not seek medical attention, believing the injury to be minor. However, over the following days, the patient continued to experience worsening headache, accompanied by nausea and occasional vomiting. The headache was described as dull and throbbing, localized to the left temporal region, and partially responsive to over-the-counter analgesics. Concerned by the persistence of symptoms, the family brought the patient to the hospital for further evaluation.

Physical Examination

On presentation, the patient was alert, oriented, and hemodynamically stable. Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was 15/15. Vital signs were within normal limits.

Neurological examination revealed

No focal deficits – Pupils equal, round, and reactive to light

- – No signs of cranial nerve involvement

- – Mild tenderness over the left temporal region

- – No signs of skull fracture or deformity

- – No papilledema on fundoscopic examination

A swelling was noted over the left temporal scalp, soft in consistency and mildly tender to palpation.

Investigations

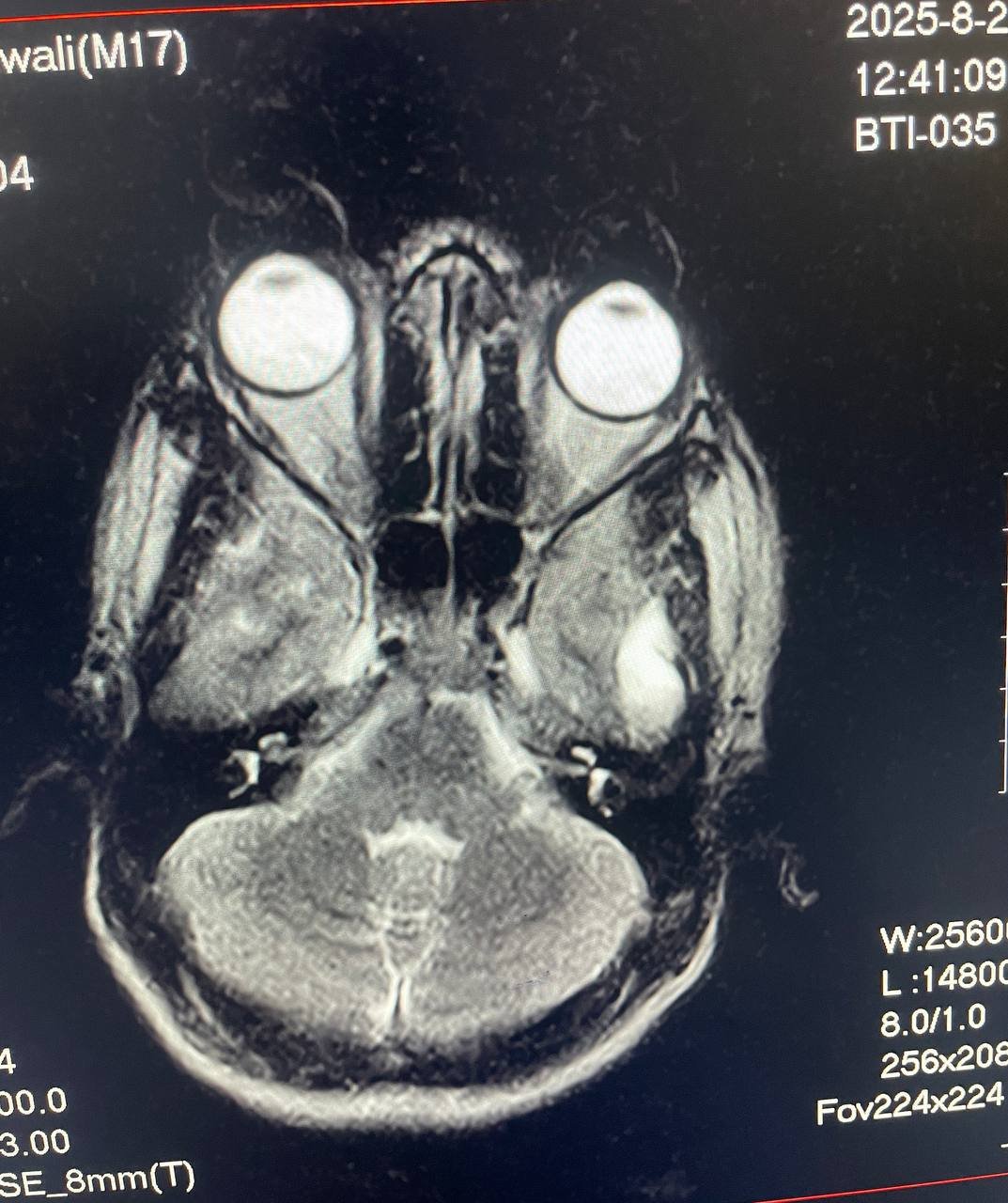

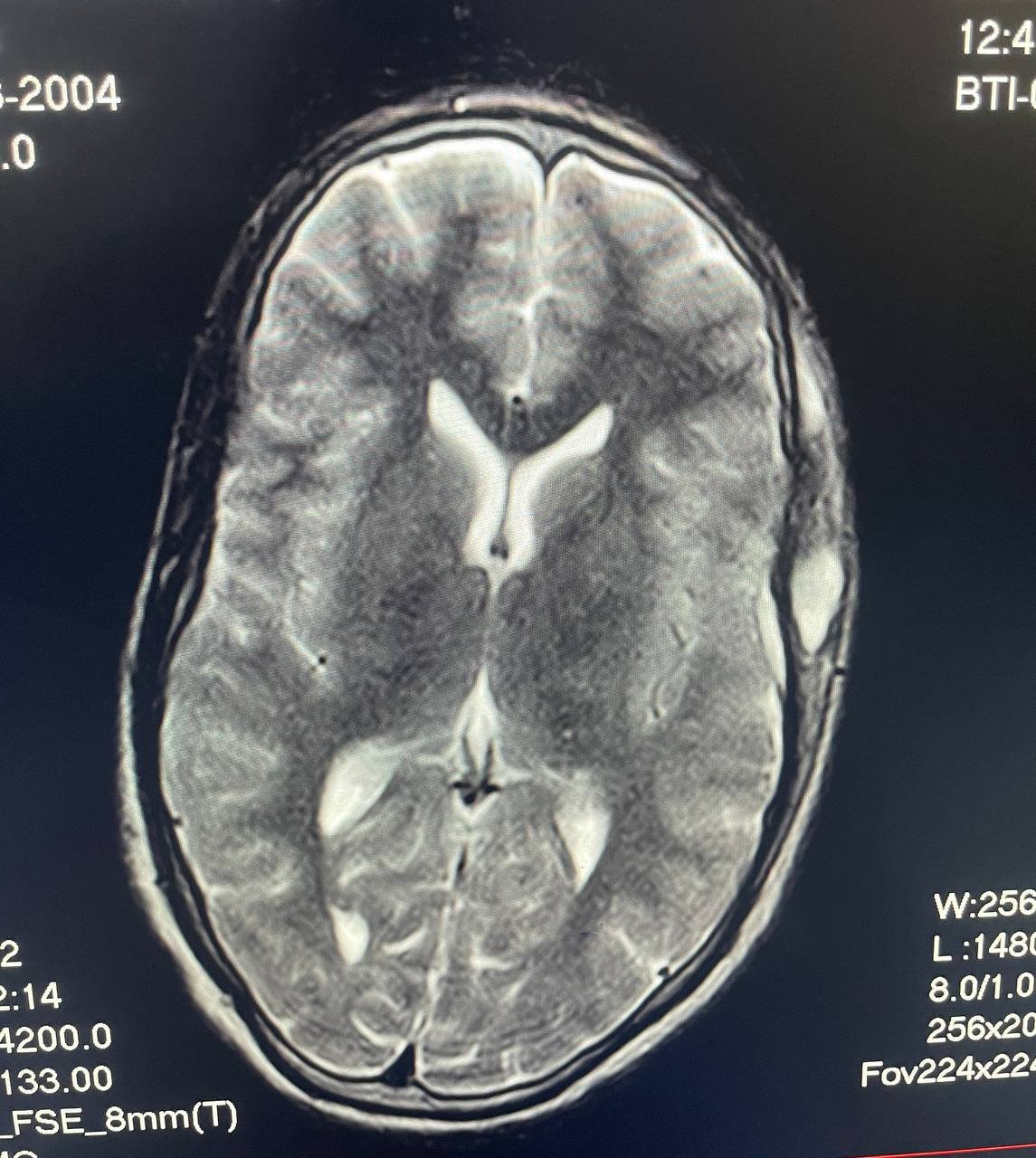

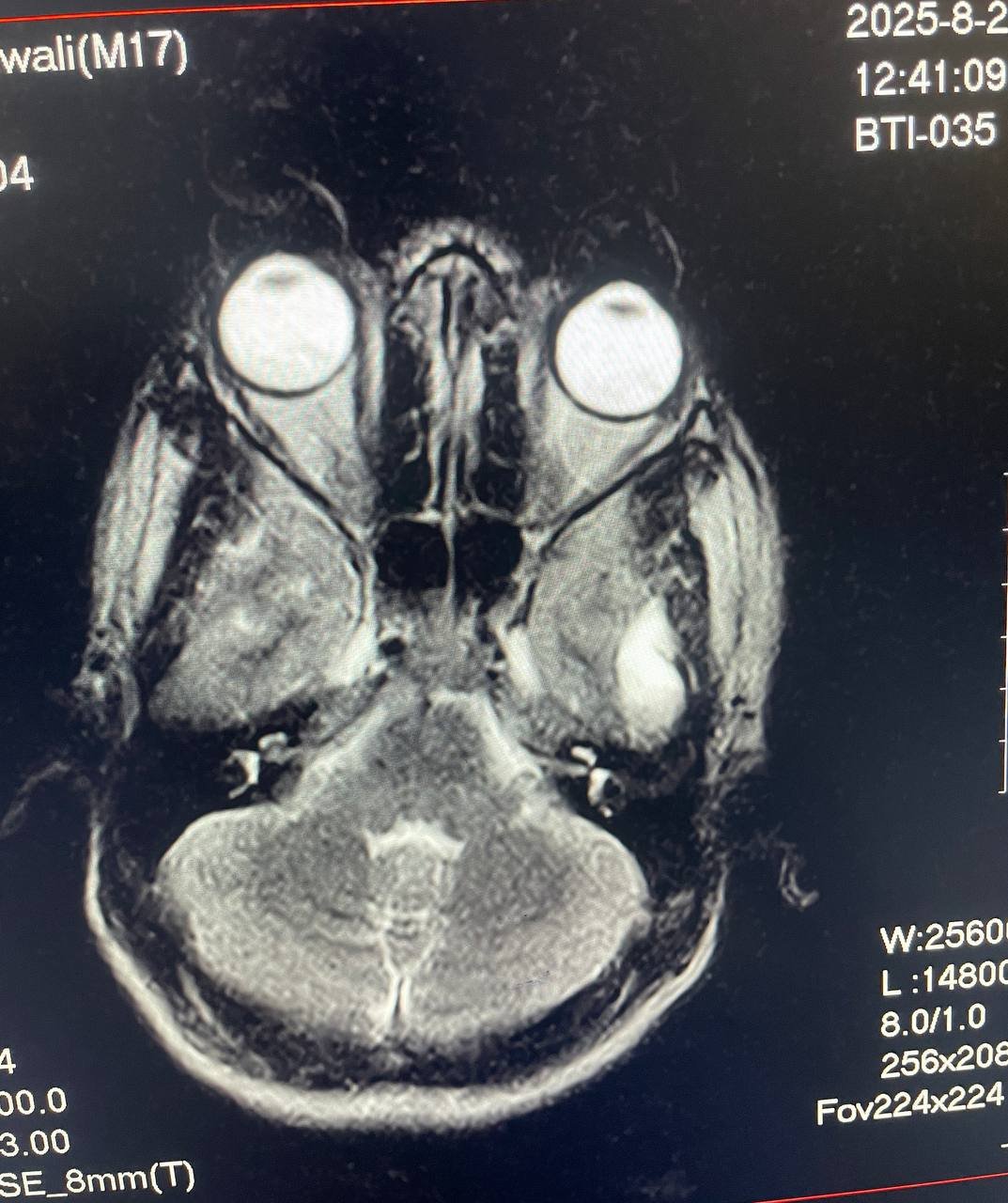

Given the history of loss of consciousness and persistent symptoms, neuroimaging was indicated. A non-contrast Mri scan of the brain was performed, revealing the following:

– A subacute subdural hematoma in the left temporal region, measuring approximately 6 mm in maximum thickness.

– No evidence of mass effect, midline shift, or brain herniation.

– Subgaleal hematoma observed over the left temporal scalp.

– No skull fractures noted.

– Ventricular system and basal cisterns appeared normal.

Diagnosis

Based on the clinical presentation and radiological findings, the patient was diagnosed with:

– Subacute subdural hematoma (left temporal region)

– Subgaleal hematoma (left temporal region)

Management

Initial Approach

The decision was made to manage the patient conservatively due to the following considerations:

– The hematoma was small in size and not causing significant mass effect.

– There was no midline shift or signs of increased intracranial pressure.

– The patient had no neurological deficits and maintained full consciousness.

– Close observation and symptomatic treatment were deemed appropriate.

Medical Treatment

The patient was admitted for short-term observation and supportive care. The treatment plan included: – Analgesics: Paracetamol and Ibuprofen for pain control.

– Antiemetics: Ondansetron as needed for nausea and vomiting.

– Neuro-observation: Hourly monitoring of vital signs, GCS, pupil response, and neurological status during hospitalization.

– Hydration and rest: Encouraged oral fluid intake and limited physical activity.

Corticosteroids and antiepileptic drugs were not administered, as there were no indications such as cerebral edema or seizure activity

Hospital Course

During his hospital stay, the patient remained neurologically intact with no deterioration. His symptoms gradually improved with conservative management. He was afebrile, cooperative, and ambulatory by the second day. Headache and nausea significantly decreased, and vomiting resolved entirely.

After 48 hours of stable observation, he was discharged with outpatient follow-up. Discharge medications included:

– Paracetamol 500 mg TID as needed for headache

– Omeprazole 20 mg daily to prevent gastric irritation

– Instructions for strict rest, no contact sports, and avoidance of strenuous activities for at least 3 weeks

The patient was reviewed in the outpatient clinic two weeks post-discharge. By then, he had experienced substantial resolution of his symptoms. A repeat CT scan was not immediately necessary due to the favorable clinical progress. He was counseled on head injury precautions and advised to report immediately in case of worsening symptoms such as confusion, seizures, persistent vomiting, or drowsiness.

Subacute subdural hematomas typically develop between 4 and 21 days following head trauma and are often underdiagnosed, especially in young individuals with minor or moderate injuries. Unlike acute hematomas, which present with rapid neurological decline, subacute SDHs may manifest with subtle or delayed symptoms, including headache, cognitive changes, and nausea. Subgaleal hematomas, on the other hand, are collections of blood between the periosteum and the scalp aponeurosis. They often result from blunt trauma and are usually self-limiting unless they are large or expanding. In this case, the patient exhibited classic features of a minor traumatic brain injury with delayed onset symptoms. The absence of a midline shift or increased ICP on imaging supported the conservative approach. Surgery is typically indicated in subdural hematomas if the hematoma is greater than 10 mm in thickness, there is a midline shift of more than 5 mm, or if neurological deterioration occurs. Early imaging and accurate interpretation are vital in preventing complications. Conservative management is safe and effective in carefully selected patients with close monitoring. In younger individuals, brain plasticity and recovery potential are generally higher, contributing to better outcomes in non-surgical cases.

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of thorough assessment and vigilance in managing pediatric head trauma. Even in the absence of initial alarming signs, a subacute subdural hematoma can develop days after injury and present with nonspecific symptoms. Imaging studies play a key role in diagnosis, while management decisions should be based on the hematoma size, clinical status, and presence or absence of complications. Timely intervention, even if non-surgical, combined with structured follow-up, can lead to full recovery, as seen in our patient. Public awareness and caregiver education are essential to ensure early medical evaluation in any case of head injury, particularly when symptoms persist or worsen.

3 Responses

This is an excellent and timely case presentation, skillfully highlighting a frequently overlooked aspect of pediatric and adolescent neurotrauma. The delayed onset of symptoms in subacute subdural hematomas (SDH), especially in young individuals, often leads to missed or late diagnoses a point well articulated here. The inclusion of a subgaleal hematoma adds another layer of clinical relevance, as such dual presentations may be underreported in similar trauma cases.

What makes this case especially impactful is the balance between clinical detail and patient-centered care. The conservative approach supported by precise neuroimaging, absence of midline shift, and stable GCS demonstrates the value of individualized treatment rather than a reflexive surgical response. The systematic monitoring protocol outlined is also commendable and should serve as a model for managing mild to moderate TBI in resource variable settings.

As a critical care nurse and ICU educator involved in remote trauma and neurocritical care training across Africa, I deeply appreciate how this report elevates awareness on subacute hematomas while encouraging proactive follow up care. Education of caregivers on red flag symptoms, especially in low resource or rural settings, is paramount and could further enhance outcomes in similar cases.

I would be honored to collaborate or contribute to future discussions or case series particularly on pediatric and adolescent trauma, ICU nursing responses to neuroemergencies, or health innovation in brain injury management.

Thank you, Dr. Gooni and the Calmmindhub team, for this brilliant contribution to clinical scholarship and public awareness.

Warm regards,

Jones Kalele, BScN, RCCN, RN, ICU, Dialysis, ER Specialist

Founder, Zambia Predictive Health Alliance (ZPHA)

Thank you so much for your thoughtful and deeply encouraging feedback.

Your insights as a critical care nurse and ICU educator working across Africa bring invaluable context and depth to this discussion. We truly appreciate your recognition of the nuanced approach taken in this case, especially your emphasis on individualized management, caregiver education, and the importance of proactive monitoring in resource-limited settings.

Your point about the underreporting of dual presentations like subacute SDH with subgaleal hematoma is well taken, and we agree that raising awareness through shared clinical experiences is essential to improving early detection and outcomes.

We would be truly honored to collaborate with you in future case series or discussions focused on pediatric neurotrauma, neurocritical nursing, or innovative strategies in trauma care across underserved areas. Your work is inspiring and aligns perfectly with the mission of Calmmindhub—to bridge clinical excellence with community impact.

Let’s definitely stay in touch and explore opportunities for joint contributions that can amplify education, advocacy, and better care across our shared regions.

Warm regards,

Dr. Gooni & the Calmmindhub Team

[…] on Real Case: Subacute and Subgaleal Hematoma After Head Trauma in 16-Year-Old BoyAugust 7, […]